By Jawad Mian, Managing Editor Stray Reflections

The inefficiencies that are at the heart of macro investing are permanent, as they relate to the inherent uncertainty of the future. The vast majority of the data required is publicly available. The differentiating factor is the ability to analyze and thematically organize the information into coherent theories. The same set of information can often lead people to different conclusions.

As always, the starting point of my investment process is complete independence of analysis and thought. I do not set out to be consensus or to be contrarian, but instead to be independent.

Hello Tomorrow

Legendary hedge fund manager Stan Druckenmiller believes that the Fed has a “golden opportunity” to raise interest rates. I agree with his assessment and suspect the hurdle for Fed rate hikes may be lower than what markets seem to presently think.

Despite the last payrolls report, I’m encouraged by trends in the overall labor market. Unemployment has fallen to a 6.5-year low of 5.5% after 12 straight months of job gains above 200,000 (the longest streak since 1994). Even if the pace of job growth stalls, the number of unemployed job seekers per job opening has fallen from 6.8 to less than 2, which bodes well for the medium-term employment outlook. Meanwhile, real wage growth is also nearly as strong as any recovery during the last 40 years.

I think both Janet Yellen and Stanley Fischer are itching to start normalizing monetary policy. The Fed usually hikes rates well before core PCE inflation hits 2% (it was 1.3% in 1999 and 1.8% in 2004). In my opinion, this time will be no different. The Fed’s preferred inflation measure has averaged just 1.7% over the last 20 years. It currently stands at 1.37%, and has been roughly stable for two years, even as core prices have slipped.

It may not seem like it now, but I believe monetary authorities have overcome the threat of deflation. They have been successful in changing people’s perceptions and breaking the deflationary mindset, even if this is not yet reflected in the level of global government bond yields. The inflation environment has been changing substantially, and it is entirely conceivable that inflation in major economic blocs will stabilize as we approach midyear and enter a slow, long-term bull market.

The Fed has created expectations that it will tighten in either June or September, and according to Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, deviation from such expectations is going to be difficult. Should the S&P 500 hover above 2,000 and oil prices stay above $50, I think the Fed will be keen to hike rates at the June FOMC meeting.

The first Fed rate hike in 11 years will mark the beginning of an entirely new investment landscape. In the near term, I believe both bond and equity markets could be at risk.

Just like we experienced a non-recessionary decline in oil prices, I would not be surprised to see a non-recessionary decline in financial markets as well this year. According to BCA Research [emphasis added]:

The first rate hike is normally ignored by the equity markets and viewed as a sign that the economy is gaining momentum. The second hike begins to generate anxiety, and the third normally begins to unsettle the market. The problem with this “ready-steady-go” framework is that this cycle is atypical. Valuations are significantly higher than when rates first started to be hiked in previous cycles. Equity markets could, therefore, suffer much quicker.

Till Debt Do Us Part

Many distinguished economists believe that emerging markets (EM) represent the most vulnerable spot in the global financial system when the Fed eventually starts tightening.

The emerging economies account for 51% of global growth today (compared with 36% in 1994), and EM corporate bond markets have expanded rapidly since 2010. Therefore, the impact from an EM debt contagion could potentially be much larger than the 1997 Asian crisis. Total dollar credit to the EM nonfinancial sector has risen from $6 trillion to $9 trillion in the past five years.

According to a study by McKinsey, total EM debt rose to $49 trillion at the end of 2013, accounting for 47% of the growth in global debt since 2007—more than double its share of debt growth between 2000 and 2007. EM debt levels have grown by 30 percentage points since 2009 to 175% of GDP.

EM previously benefitted from both a positive economic and credit upcycle, but this has left many of them with a significant resource misallocation and declining returns on capital. Too many countries are funding their current account deficits by short-term capital inflows, therefore elevating sovereign risk and leaving them susceptible to swings in investor sentiment.

EM currencies have already weakened substantially against the US dollar since 2011. If the dollar continues to rise unabated, the dollar cost of funding for EM external liabilities will also rise in tandem.

For example, an EM firm borrowing $10 million via a 10-year bond with a 5% coupon must pay $15 million over the life of the bond. But if the local currency falls 50% against the dollar, then the payment required in local currency to pay off the dollar loan actually doubles in value.

Now consider that in the past two years alone, the Turkish lira is down 44%, the Brazilian real has lost 58%, and the Russian ruble has crashed 83%.

Are investors suffering from a collective cognitive dissonance when it comes to emerging markets?

My dear friend Marko Papic explains [emphasis added]:

Cognitive dissonance is the psychological state of holding at once two or more contradictory ideas or beliefs. For example, investors continue to plow portfolio flows into EM despite clear signals of underperformance from the currency markets and their weak macroeconomic fundamentals. Human beings tend to strive for internal consistency by suppressing contradictory information that would exacerbate the dissonance. At some point, however, the dissonance can be resolved only with a dramatic psychological break. I believe politics could provide such a catalyst, especially as social unrest and angst mount in the EM space in the coming months. The longer investors ignore the inevitable adjustment with blind commitment to EM financial assets, the worse the eventual break will be.

As Worth Wray reminded me recently, never forget Dornbusch’s Law: The crisis takes a longer time coming than you think, and then it happens faster than you would have thought.

This Time Is Different

I believe recent weakness in EM does not herald a repeat of the 1997 Asian crisis. I don’t think a Fed interest rate hike will lead to a disorderly carry trade unwind, an EM debt crisis, and another global recession.

What made the 1997 period so unique was that we had an abrupt “macro regime change” set off by the currency devaluation in Thailand. Models and assumptions that worked until then were suddenly no longer valid. Recall that two-thirds of EM countries had pegged exchange rates. There was a massive shock to the system as leverage and built-up excesses were quickly unwound.

This time is really different.

EM currencies have been in a downtrend for over four years, investors have shunned EM stocks since 2013, and global banks that have made loans face far tougher regulations and are generally better capitalised. Therefore, I suspect there are no real skeletons left in the closet.

Market practitioners are largely aware of fundamentally weak economies with poor growth prospects and large external deficits. Investors have been adapting to the macro environment and punishing EM transgressors.

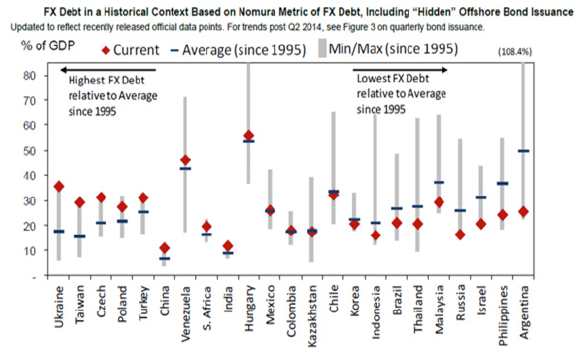

According to Jen Nordvig’s team at Nomura, with overall debt levels fairly low, the problem for the major EMs is not one of national creditworthiness [emphasis added]:

A major mitigating factor is the fairly low overall level of EM dollar debt, especially relative to foreign exchange reserves. EM sovereign debt, as distinct from corporate debt, has been significantly reduced in recent years, and large reserve cushions have been built up.

Although EM external debt is back to mid-1990 levels, it has declined as a share of GDP, and EMs are less exposed to currency mismatch risks than they were in the 1990s. Economists at Morgan Stanley studied the accounts of 762 firms across Asia and found that on average, whereas 22% of their debt was dollar denominated, so was 21% of their earnings—despite Asian firms’ foreign-currency debts rising from $700 billion to $2.1 trillion between 2008 and 2014.

Most important, I now believe the risk of a one-off Chinese devaluation is also off the table. Last month, China’s yuan posted its biggest monthly gain since December 2011, and the PBOC is making more public overtures to make the yuan a global reserve currency.

While I don’t expect financial stress in the emerging world to snowball and threaten the global economy and financial system as it did in the past, I cannot rule out further bouts of market volatility. In fact, I actually welcome it.

The Long View

Ecstrat founder John Paul Smith and his colleague Emad Mostaque believe that even though valuations are now much cheaper than in developed markets, the time to become more positive on emerging markets has not yet arrived, as the major structural drivers for the asset class are still mainly negative. I quote from their EM strategy initiation report published in October 2014:

The shift towards more state-directed capitalism, which has taken place across much of the emerging world since 2008, has undermined one of the key defining features of emerging markets as a distinct asset class, namely the gradual convergence of EM governance regimes towards so-called Anglo-Saxon norms.

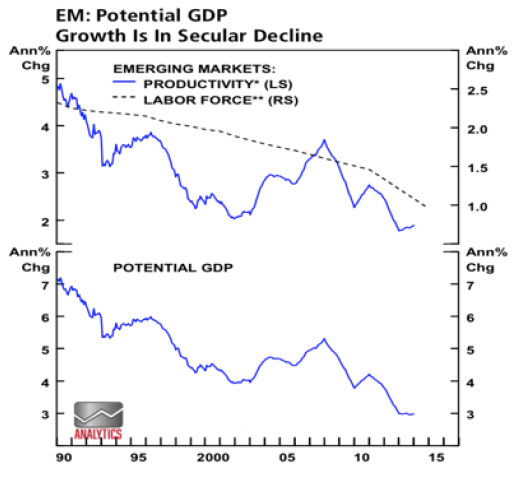

The major reason for the EM underperformance over the past five years has been the unwillingness of policymakers across the major emerging markets to implement the capital-friendly structural reforms, which are necessary to shore up productivity growth (and equity returns).

In my view, valuations aren’t as compelling as they appear at first glance, either.

Consumer and healthcare stocks, which generally boast more attractive growth and governance characteristics according to Ecstrat, are very expensive and trade at a valuation premium on a global basis. Meanwhile, financials and energy are cheaply priced for good reason—their outlook is impaired by cyclical headwinds or state meddling at the corporate level.

With my global purview, I find far more attractive opportunities in European and Japanese financials or US energy plays. Established consumer brands and healthcare stocks in the developed world also deliver a higher rate of return on invested capital.

Why invest in EM companies where control structures are weak and the interests of minority shareholders have a history of being subordinated at the whims of the majority shareholders?

The quality of political, legal, and corporate institutions is crucial to investing in emerging markets. According to Marko Papic, without sound institutions, annual GDP growth could be N%, but most of the earnings could seep in inefficient state-owned enterprises, populist public expenditures, and corruption. Laissez faire can no longer be taken for granted.

I need to see conditions ripe for policy change to turn full-stop bullish on EM assets. For now, there is little indication that policymakers are prepared to introduce the pro-market reforms necessary to reverse the secular decline in productivity and potential GDP growth.

The process only seems to be underway in China, India, Mexico, and Philippines.

No Curtain to Hide Behind

Alas, I don’t see economic tensions and uncertainties in the emerging world receding any time soon.

I am looking intently for credible policy regimes and signs of improvement in governance to restore confidence in financial markets and achieve acceptable rates of growth and profitability.

However, I fear a market riot may be necessary to force officials across EMs to implement far-reaching reforms.

I think more and more EM countries will eventually adopt the new Chinese model of “state-owned but not state-directed” to enhance corporate governance and enable the government to distance itself from the management of many key enterprises without relinquishing ownership.

Within the EM space, I would prefer: 1) reformers over populists; 2) Asia over Latin America; and 3) commodity consumers over producers.

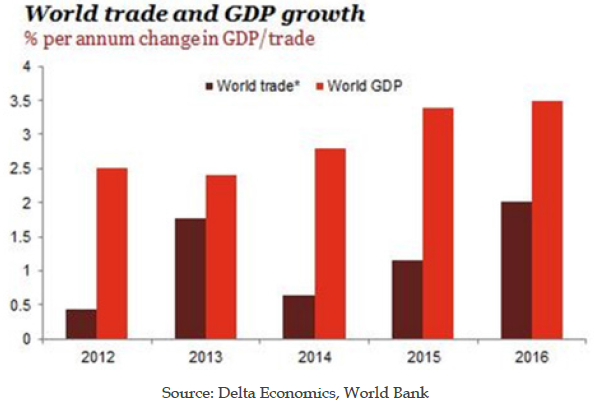

With global trade volumes growing slower than global GDP since 2012, I also favor EM countries that are less reliant on exports and that have a better ability to stimulate domestic demand. I see a growing importance of services trade over manufactured goods, and economies that are sufficiently geared to benefit from that trend should also do well over time.

“Strong Hands” and EM Adjustment

Looking at the profile of previous relative bull and bear markets in EM versus global stocks, I suspect emerging markets have completed two-thirds of their underperformance in the current market cycle. The relative bull market ended in 2011, and asset allocators have been generally underweight EM stocks since 2013.

According to the Bank of America Merrill Lynch Global Fund Manager Survey, the proportion of asset allocators underweight global emerging markets has risen to 11% from 1% in the past month, with 57% of the global panel saying that global emerging markets is the regional asset class they most want to underweight in the coming 12 months—down from a net 63%, but remaining close to historic survey highs.

The 15 leading emerging economies saw $392 billion in net capital outflows in the second half of last year, according to data compiled by ING. This compares to $545 billion in capital outflows over three quarters during the 2008-2009 crisis. Although this was the largest absolute capital outflow since the global financial crisis, EM have not seen net portfolio outflows since 2008 on an aggregate basis.

I believe this is mainly because most EM debt is owned by deep-pocketed, long-horizon institutional investors such as pension funds and insurers. Even with weak macroeconomic fundamentals and massive currency losses, a dearth of alternative investment options means investors are reticent to change their behavior.

I can imagine turning positive on local-currency EM debt after a shakeout of weak hands as accommodative policies by EM central banks may lead to significant carry gains in my view. I think inflation will begin to decline even in places where it has been structurally very sticky such as Brazil and Turkey (two of the largest markets in investible local-currency EM).

According to BNP Paribas, current bond prices suggest investors expect the rate of default for non-investment grade EM bonds (about a third of the total) to rise from 2.8% to 12% in January 2017. This seems excessive to me.

EM Currency Index

Source: Tiho Brkan

With currencies down 30% on average, I also think that we may have seen the bulk of the currency adjustment in the EM space.

The Stray Reflections Philosophy

Stray Reflections is a global macro advisory publication with a focus on major investment themes and actionable trade ideas. My primary objective is to achieve long-term capital appreciation by identifying a diversified portfolio of trades that each add incremental alpha for our clients.

The investment environment is changing at a rate that’s representative of global economic imbalances, fund flows, and geopolitical risks. Very few past models are still valid and such a situation has contributed to the extreme uncertainty that currently prevails. With Stray Reflections, my guiding principle is to help investors understand and navigate through all the complexities of an unstable, deflation-prone world.

You can begin receiving Stray Reflections each month by clicking here.