By Marshall Sonenshine, Chairman and Managing Partner at Sonenshine Partners.

1. Market Forces: Advising the CEO in an Era of Shifting Understandings of Leadership

We deal makers represent and counsel CEOs, who are generally unusually talented and demanding people from whom in turn much is demanded. We do this in markets that are often shifting quickly

in ways that can redefine the mandate of CEOs. Indeed, CEOs today work in an environment in which information flows freely, markets react continuously, and in many critical periods of time, finance can often displace real economic factors affecting companies. Consider several rather dramatic macroeconomic factors all at work at the time of this writing:

• As the first decade after the 2008 financial crisis concludes, interest rates are at such historic low levels that in many swaths of the global government bond market, they are actually negative, something

essentially unheard of in modern capitalism. Low rates have forced a rotation of capital from fixed income to equities, driving up corporate stock valuations and leaving institutional investors on a search for

returns, by increasingly pressuring companies and their CEOs to wring out inefficiencies, deliver dividends, and consolidate. Markets are metaphorically in the C-suite.

• Shareholder activist funds have grown rapidly, well past $150 billion in the United States, and institutional investors worldwide continue to demand governance and strategic and financial changes to corporations.

• Great Britain voted to leave the European Union after decades of membership, driving the pound sterling down 10 percent and the Dow Jones Industrial Average down 600 points in a single day. Geopolitics whipsaws the metrics of business.

• Economic growth and public policy shape management. Growth in most markets after the 2008 financial crisis remains anemic, job recoveries in the United States mask low work participation rates, tax inversion deals were all the rage and then suddenly restrained, and antitrust authorities that had been quiet are now active.

In a word, in today’s economic environment things change dramatically for CEOs navigating global strategy and deals.

The range of shifts in market and governance assumptions today is too broad to discuss in a short essay, but two shifts are worthy of comment here: the growth in M&A as a core competency of modern corporate life and the rise of shareholder activism as a check on CEO and board power.

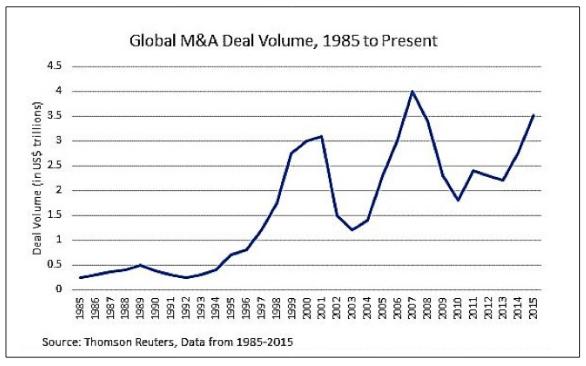

M&A is now core to management. A generation ago M&A required specialized knowledge mostly held by bankers and lawyers, whereas today virtually all large cap companies and most upper-middle-market and even many middle-market companies view M&A as an ordinary part of their business and employee executives and managers with meaningful M&A experience. This shift is a direct result of the shear growth of mergers, alongside broader equity market growth, over the past few decades.

Today, many companies are comfortable executing buy-side deals without the assistance of buy-side bankers. Acquisitive companies increasingly employ ex-merger bankers specifically to cut out the outside bank. Comcast hired its former senior M&A banker as its head of M&A in 2016 and virtually immediately acquired DreamWorks for $3 billion with no external investment banking adviser except to provide a fairness opinion. Companies and private equity firms still routinely use bankers for the more labor-intensive task of selling businesses, but buying is now a narrower market for bankers. In this new context, many bankers have been reduced to “task,” though the best ones are still valued for judgment and insight.

Second, the proliferation of boutique bankers has made it more customary for companies, when they choose outside advisers, to look at individual talents of individual practitioners much as they do in retaining law firms or other advisers. The deal business may be at once more meritocratic and more personal today than ever before.

A generation ago, the Harvard Business School professor of investment banking, Samuel Hayes III, reviewed a curious survey asking clients and their bankers separately what caused their business partnership. The divergence in the responses from each constituency surveyed was telling: bankers imagined they had been hired for their relationship building. They cited that they really knew their clients personally, spent time with them, and earned their trust on a personal level. That may be true, but clients tended to explain their choices with reference to good old task: The firm they hired got things done that the CEO and the company needed to get done. Hayes found that clients said far less about the relational elements on which their bankers had prided themselves. Perhaps today, because there are many ways to hire execution services, the answers at least sometimes might be more integrated and less

divergent from both constituencies—that is, perhaps clients and bankers would agree that advisers just possess a particular blend of execution skill and personal trust to get the nod.1

Market voices are now in the C-suite. Beyond the core nature of M&A now, something else is at work today, something far broader and more consequential about the very nature of leadership. As noted earlier, the age of activism has replaced the era of entrenchment and imperial governance of companies with the current era of accountability. As these market forces have mounted, legal impediments to shareholder democracy have been dismantled, starting with easier access to corporate proxy machinery in the early 1990s and continuing through ISS and other shareholder voting blocs in today’s market. The evidence is overwhelming: Boards have been de-staggered and include more outside directors; CEO tenures have often been cut short or companies reorganized or sold under activist pressures; poison pills have been redeemed or simply not renewed, to the point of near disappearance; and even relatively small shareholders have been able to drive large changes, often over CEO objections.

In the past few years numerous companies have chosen to negotiate board seats with activists in lieu of waging what might be losing proxy fights. In one notable choice, when top activist fund Trian took a stake in GE, GE CEO Jeffrey Immelt invited Trian to make a presentation to GE executives on its views on corporate change. In the hands of lesser CEOs than Immelt, this accommodation might have been seen as a sign of weakness, though in Immelt’s case it was a sign of his confidence as CEO and his realism about market expectations that CEOs show openness to key investor views.2 The winds had shifted decidedly in favor of openness to ideas and enhanced accountability to institutional investors, including for first-tier CEOs.

The restatement of CEO powers mirrors a restatement of presidential and other government powers in the post-2008 crisis era as ultimate constituents (voters are the shareholders of democratic governments) have voted to take back power and ramp up accountabilities. Here again, the evidence is unmistakable, whether one focuses on Donald Trump’s end run around the Republican Party, Bernie Sanders’s notably well-supported challenge to the Democratic Party establishment, or the momentous vote by British citizens to exit the European Union in direct contravention to the advice of both a sitting Prime Minister and his opposing party leadership. These watershed events in the public sphere mirror the shift in power toward ultimate constituencies in the corporate sphere.

Where, then, is leadership today in the corporate and public spheres? It is in the throes of a correction from centralized power to greater accountability to ultimate stakeholders—owners in business and voters in politics. This is not a bad thing, nor in all cases, an efficient thing. This is a cultural trend, a tectonic shift reflecting digital information flow and constituency demand, to be understood by business leaders and their advisers. Today, the adviser to the CEO must reflect, to his or her client market, pressures on the CEO. The adviser must know to which pressures the CEO might bow and to which he or she might buck. The adviser must know how to deliver strategies and opportunities that can add value, including value that may not be immediately apparent to activists or other public market participants. His or her job is more nuanced, more complex, and more driven by accountabilities because his or her clients’ jobs are as well.

In this era of new leadership nostrums, of new challenges for business leaders and their advisers, we are all on new footing, saddled with market forces that are more present in the board room, the C-suite, and the banker’s briefing materials than ever before. This is the new essence of leadership now, at this time, in the long game of business.

2. Practice: Deal Makers and Their CEO Clients

To develop and negotiate deals, one must develop and deal with people. That does not mean deal makers are necessarily emotionally balanced people. Some are, and others are not. Like their CEO clients, they may be anything but balanced. But at least when on the job, they must not only understand strategic, financial, legal, and market issues; they must also be able to read the room, win confidence, discern unstated motives, and negotiate outcomes. They must represent, support, and advise CEOs and sometimes correct their faults. Their ability to navigate among those differing modalities defines their results as leaders of a sort different from their clients.

What, then, are we to make of the intense odd couple—the sentient and role-shifting deal maker as adviser to the mostly task-oriented but also sentient CEO? The pairing is always important, for this team is among the most symbiotic in business life, at least during the term of a deal’s process. To his or her CEO client, a deal maker is part muse, part consigliere, part mouthpiece, and part servant. To his or her staff of underlings the deal maker may be their CEO. And to the broader board of directors and owners, the CEO is a fiduciary, though ultimately all deal actors on behalf of companies—CEO, other executives, bankers, and lawyers—are hired help.

The deal maker is an obsessive task master and task doer. He or she has to be. Deals comprise numerous tasks that must be managed and executed. But tasks alone will never create a deal; tasks can only execute a deal inspired by more gooey material relating to people, business dynamics, and the negotiation of what John Maynard Keynes called “animal spirits.” Thus, the subject of leadership in the deal context is complex because leaders play multiple roles in relation to multiple parties. That is why deal people are so interested in the topic of leadership: Deal people serve leaders, negotiate with other leaders, lead teams, and follow orders, often all in a single day’s work. The present fifth edition of the Best Practices of the Best Deal Makers series thus appropriately takes a microscope to leadership as its own topic within deal making. After all, deal makers lead deals that often transform whole companies and even industries, but they advise and mediate among CEOs, who lead much larger enterprises and are used to calling most of the shots. That is complex stuff, indeed.

about the author: Marshall Sonenshine is Chairman and Managing Partner at Sonenshine Partners. Prior to founding Sonenshine Partners, Mr. Sonenshine was a Partner in BT Wolfensohn, the mergers and acquisitions Department of Bankers Trust (“BT”). At Bankers Trust, Mr. Sonenshine headed the firm’s media and transportation mergers and acquisitions practices as part of the bank’s global investment banking arm, BT Alex. Brown, and its successor organization, Deutsche Banc Alex. Brown, where he was asked to be Co-Head of Mergers and Acquisitions. Mr. Sonenshine has advised on leading M&A transactions globally. Mr. Sonenshine is also Professor of Finance and Economics at Columbia University.

This is an extract from “Dealing With The CEO”, the introductory chapter of the 5th Edition of this series – Leadership in Modern M&A: Exclusive Insight from Global Dealmakers. “The Best Practices of The Best M&A Dealmakers” series profiles the proven strategies and unique experiences of the leading M&A practitioners, and is distributed in regular installments for M&A industry professionals in both print and interactive electronic media. Previously published features and chapters are also available in the online library of Merrill Corporation and The M&A Advisor.

about the sponsor: Merrill Corporation helps global companies secure success. From the start to end-to-end solutions – we simplify the complexity at every stage of the life cycle of regulated business communications. Whether you are looking at M&A or an IPO, filings with the SEC or other regulatory bodies, wanting a better way to manage contracts, IP and assets or looking to engage and communicate with customers – Merrill has the breadth and depth of services to unlock productivity. From implementing proven methodologies to forward thinking technology. From the current regulatory landscape to what’s coming down the line. From day one to 24/7/365 expert access. Learn

more by visiting www.merrillcorp.com

1. See Samuel A. Hayes, Michael Spence, and David Van Praag Marks, Competition in the Investment Banking Industry (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983) (reviewing survey conducted by Professors Dwight Crane and Robert Eccles).

2. See, e.g., Peggy Hollinger and Miles Johnson, “Activist Nelson Peltz Takes Stake in GE” in Financial Times online Oct. 5, 2015.

related content: