By Mary Bates, Director of Credit Strategies at Silver Creek Capital

As interest in liquid alternatives surges and the search for yield continues, public Business Development Companies (“BDCs”) have received significant institutional interest. These REIT-like vehicles, which have historically focused on the retail market, appear very attractive at first blush, offering yields above traditional high yield debt with daily liquidity. But, as the saying goes, appearances can be deceiving – and, we would offer, expensive.

Silver Creek has invested in multiple private BDCs that have gone public, and we understand the space and the nuances of the vehicle well. Here, we share our thoughts on why we believe that public BDCs are often an expensive high dividend stock substitute rather than a private debt “liquid alternative.” We also highlight how in certain instances public BDCs may opportunistically be attractive investments.

The What & WHY of BDCs

Fitch Ratings wrote a comprehensive primer on BDCs in September 2006 titled “The ABCs of BDCs.”[1] Although it is nearly 10 years old, the publication remains an industry standard and one that we will not attempt to recreate. Rather, we begin by highlighting the “what and why” – i.e., the rules that make a BDC a BDC, as well as the investment thesis. As both topics have been well-chronicled (and dry), we will keep this section brief and hit only the key highlights.

THE WHAT

A BDC is an investment vehicle that primarily invests in middle market private companies through originating and holding debt investments until maturity. Although they have been largely focused on middle market direct lending, the vehicles retain the flexibility to invest across a company’s capital structure. In addition to senior loans, many BDCs also hold mezzanine debt, equity, and a variety of other instruments (including structured products). BDCs, much like REITs, pass through nearly all of the income associated with the underlying investments in the form of monthly or quarterly dividends.

Created by Congress in 1980 to allow public investors to invest in private companies, the following key rules define a public BDC :

- At least 90% of taxable income must be distributed to investors as dividends in order for the BDC to avoid corporate level taxation;

- Leverage is not to exceed 1:1 debt to equity;

- At least 70% of the assets must be unlisted or with companies with a market capitalization of less than $250 million;

- Subject to certain provisions of the Investment Company Act of 1940 relating to closed-end vehicles;

- Subject to diversification requirements (greater than 50% of the portfolio must be in position sizes less than 5%; no position can be greater than 25%);

- Meet the reporting requirements of any public company (10-Ks, 10-Qs, etc); and

- Comply with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002.

THE WHY

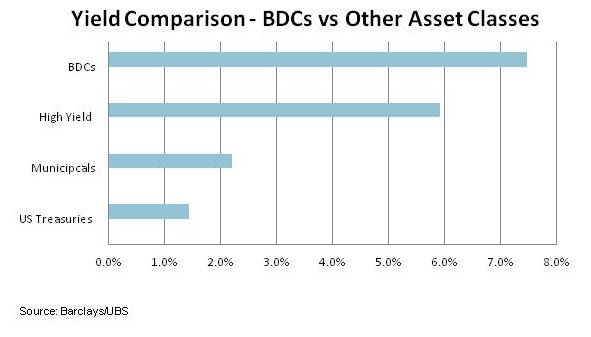

Given the required distribution of taxable income, many investors are attracted to public BDCs because of the perception of a stable attractive yield. As shown below, public BDCs currently compare favorably to other traditionally yield-oriented asset classes on a simple yield comparison basis. On average, BDCs currently offer a 1.6% yield premium to high yield bond funds and over 6% to U.S. Treasuries .

While yield is the primary draw for most public BDC investors, other attractive features may include daily liquidity, low leverage (relative to other financial service stocks), portfolio diversification, transparency, and the prospect for moderate capital gains.

THE ARGUMENT

The “what and why” of public BDCs is seemingly compelling. But is high yield the correct framework for comparison? Are the fees comparable? What about the correlations? We explore these questions and others below.

FEES (Or Making Hedge Funds Look Inexpensive)

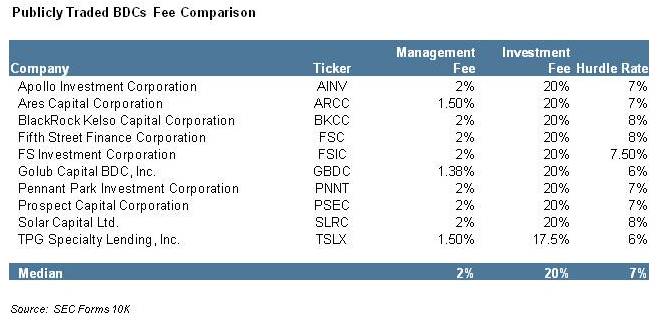

Although BDC managers compare themselves on a yield basis to high yield and other traditional income strategies, their fees are anything but traditional. The fee structures are similar to those of an alternative asset manager, having both a management fee (i.e., an asset-based fee) plus an incentive or performance fee. Similarly, the absolute level of fees for a typical public BDC is more in-line with hedge fund managers than with traditional managers – albeit actually higher than hedge funds. Historically, the industry standard fee structure for hedge funds has been “2 & 20”: a 2% management fee and a 20% incentive fee. According to Deutsche Bank, the new standard in the hedge fund industry has declined slightly to a management fee of 1.69% and an incentive fee of 18.21%.[1] By comparison, the median fee for the largest public BDCs remains at 2% management fee and 20% incentive fee with a 7% hurdle rate.[2] (Hedge funds typically do not have hurdle rates).

It is certainly notable that public BDCs appear to have higher fees than average hedge funds. However, what is more striking is the basis upon which public BDC management fees are charged. The industry standard for hedge funds is that the asset-based management fees are charged on the net asset value, or equity of the fund. In private debt funds, the management fee is often charged on invested (as opposed to committed) capital. In contrast, the industry standard for public BDCs is for management fees to be charged on gross assets — i.e., the total leveraged amount of assets. All of the public BDCs listed below follow this industry standard. To put this in perspective, assuming a BDC manager employed a 1:1 leverage ratio (the regulated maximum), the total annual management fee would be closer to 4% of equity. A further point to consider is that many public BDCs charge incentive fees quarterly or annually on realized and unrealized gains and there is not typically a look-back provision. Again, this is more expensive for the investor relative to private debt where the industry standard is for performance fees to be charged only on realized gains.

In short, there is nothing traditional about public BDC fees. Moreover, given that management fees are paid on gross assets, public BDCs make hedge funds look inexpensive by comparison!

CORRELATIONS (Or Is this a really private debt??)

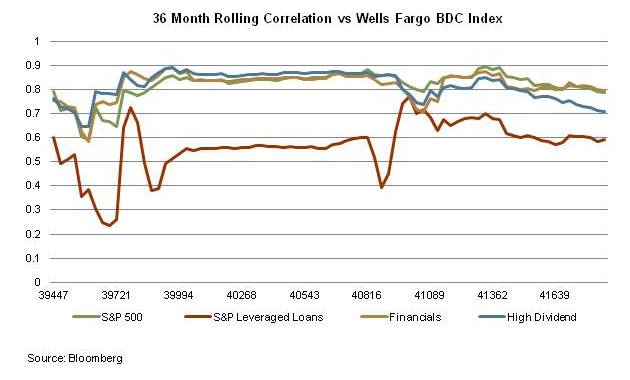

While public BDC fees are clearly high, investors may be willing to pay higher fees for a return stream that has diversification benefits to their overall portfolio – i.e., something with a low correlation to other portfolio assets. Public BDCs appear to have limited diversification benefits. Said differently, public BDCs “act” quite similarly to equities and financial stocks in particular. As illustrated below, over the past 36-month period, public BDCs have an average correlation of 0.79 to the S&P 500. The correlation between public BDCs and financial stocks and high dividend stocks is nearly equally high, while the correlation with leveraged loans is notably lower. Specifically, the rolling 36-month correlation between BDCs (using the Wells Fargo BDC Index as a proxy), and bank loans (using the S&P Leveraged Loan Index as a proxy) averaged approximately 0.5 for the time period below.

The Counterfactual

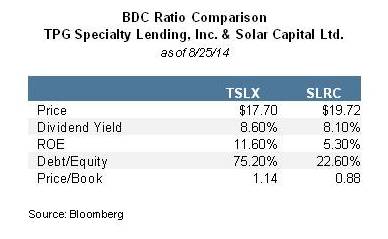

With high correlations and even higher fees, the case against public BDCs appears strong. But correlations do not imply causation, and many factors impact the price of a stock. Take, for example, how TPG Specialty Lending, Inc. (ticker: TSLX) and Solar Capital Ltd. (ticker: SLRC) have traded recently. As highlighted below, both stocks have had similar dividend yields. However, SLRC has significantly lower leverage than TSLX. SLRC is currently trading at a discount to book value (BV), while TSLX is trading at a premium to BV. Investors do not appear to be appropriately differentiating these two BDCs in terms of leverage, creating a potential investment opportunity.

Silver Creek regularly reviews lending businesses that utilize private BDCs as their investment structure. Many of these private BDCs have as a central part of their business plan an agenda to make their Initial Public Offering (IPO) when the market is receptive. It is our view that this private-to-public arbitrage can be an accretive driver of returns in quality lending businesses. Silver Creek funds have invested in several private BDCs that have been monetized via a sale of public shares. We invested, in part, because of the optionality associated with potentially capturing a premium to BV via the public markets. Our funds also have participated in a private BDC where our funds have been partial owners of the management company and participated in a revenue sharing agreement once it went public. In all cases, we were not dependent upon an IPO to exit and structured a definitive wind-down clause if there was not an accretive IPO. Moreover, our BDC investments have been predicated on underwriting the underlying investment strategy via disciplined loan level analysis, and our investments have been done with managers who we consider as best-in-breed in private lending. Solid, conservative underwriting drove these investments, the prospect of an IPO was not weighed heavily in the process.

We also see opportunities in public BDCs that meet our strict underwriting standards if or when they trade at a significant discount to BV. (In our experience the “meet our underwriting standards” screen has been a high hurdle that few of today’s public BDC’s would meet.) A third option for utilizing BDCs, in our opinion, is as a hedge. If we enter a market environment (for example, in 2006) where BDCs trade at significant premiums to BV, then shorting the public BDC can be used as a hedge against private lending businesses.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

On their face, public BDCs may appear attractive, offering a premium to broadly syndicated credit with daily liquidity. But appearances are deceiving and the cost of leverage and liquidity is often quite high. With typical management fees nearly twice that of hedge funds and correlations to the broader equity market close to one, we think public BDCs are generally best thought of as an expensive, high dividend financial stock. That said, Silver Creek has capitalized on private-to-public arbitrage opportunities in the space and recognizes certain instances in which public BDCs may be attractive investments on an opportunistic basis.

[1] “The ABCs of BDCs,” Fitch Ratings, September 2006. Meghan Crowe, Christopher Wolfe, William Artz.

[2] Source: Deutsche Bank Markets Prime Finance, Twelfth Annual Alternative Investment Survey; February 2014.

[3] Median fee calculation based on fee comparison of 10 of the largest public BDCs. Source: SEC Forms 10K.

[4] Source: Deutsche Bank Markets Prime Finance, Twelfth Annual Alternative Investment Survey; February 2014.

[5] Median fee calculation based on fee comparison of 10 of the largest public BDCs. Source: SEC Forms 10K.

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute an offer or a solicitation of an offer to buy an interest in any fund managed by Silver Creek Capital Management. Silver Creek Capital Management does not necessarily have access to information from third-party managers to ensure the accuracy of the information presented, and any information received from third-party managers is unaudited and may be inaccurate or incomplete.