Waiting to turn trash into treasure

“THIS is going to be the next great trade,” one American hedge-fund executive effused early this year. For more than two years funds have been salivating over the slew of assets that Europe’s banks will have to sell. Many have been opening offices in London and hiring to prepare for this “tidal wave” of opportunities.

Up for grabs will be distressed corporate loans, property debt and non-core businesses as European banks shrink their balance-sheets to meet stricter capital requirements. Huw Van Steenis of Morgan Stanley estimates that banks will have to downsize their balance-sheets by €1.5 trillion-2.5 trillion ($2 trillion-3.4 trillion) over the next 18 months. Funds have only about $150 billion to spend on distressed debt in Europe, he reckons, which means they should have their pick of assets.

For now the “next great trade” is not looking that good, mainly because there have been no fire sales. Most banks that are selling assets have priced them close to face value, providing little to entice buyers.

Even where sales are agreed, financing is scarce. In July Blackstone, a large alternative-asset manager, agreed to buy a £1.4 billion ($2.2 billion) real-estate loan portfolio from Royal Bank of Scotland, but has yet to raise an estimated £600m to pay for it. Worse still, many banks may not be able to sell assets cheaply even if they wanted to, because it would force them to take losses that would erode scarce capital.

“We’ve been lying in wait for this opportunity since 2008. But it will come piecemeal. It will take years and years and years,” says Joe Baratta, head of European private equity at Blackstone. Some predict that Europe could go the way of Japan’s glacial deleveraging and take a decade or more to clean up its banks. Politics play a role too. European politicians, no hedge-fund lovers, won’t want to see them buying up assets at truly distressed prices and profiting from Europe’s gloom. It may even be “politically impossible” for banks that got a government bail-out to write down assets significantly, says Jonathan Berger, the president of Stone Tower, a $20 billion alternative-asset firm.

What could turn things around? Some fund managers hope a plan to recapitalise Europe’s banks to the tune of €106 billion by next June will at last force disposals at banks. So too may the introduction of Basel 3 rules that will require banks to hold more high-quality capital. Marc Lasry, the boss of Avenue Capital, a distressed-debt hedge fund, wants to buy from these “forced sellers”, because they will offer lower prices.

Banks aren’t the only prey that funds are hunting. A wave of refinancing that will hit private-equity-owned firms over the next few years may prove profitable for distressed-debt funds. And plans by some European governments to privatise infrastructure assets may also be enticing.

In the meantime, inventive fund managers are figuring out other ways to do deals. Some, such as Highbridge, a large American hedge fund that is owned by JPMorgan, and KKR are scaling up their lending operations as banks cut back. They are able to charge high interest rates, because companies are desperate for cash.

Banks are being inventive too. Unable to sell assets, they have come up with a compromise of sorts, and have started agreeing to “synthetic risk transfer” arrangements with hedge funds. For example, BlueMountain Capital, an American hedge fund, has agreed to take on some risks on a credit-default swap portfolio from Crédit Agricole, a French bank. Another hedge fund, Cheyne Capital, has reached an arrangement with two big banks in Europe to take the first 4% or so of losses from a securitised portfolio of loans, in exchange for a very healthy return.

For those hedge funds set on playing Europe, the main dilemma they face is how long to wait before buying. Steve Schwarzman, the boss of Blackstone, insists that it is important to stay put. “It’s like dating someone,” he says. “You can say let’s wait two years. But she probably won’t be around then.”

The deal flow resulting from the partly state-owned British banks reducing their assets has been slower and smaller than many expected. This is partly because the banks have effectively lobbied to have new capital adequacy regulations phased in over a longer period than first thought, and because the regulations which seem onerous in high principle on their announcement seem less so when the detail means of implementation locally are made public. In sum, along with accumulating retained earnings, there is less risk of a capital shortfall for these banks than there was, so the pressure to conduct asset sales does not come with a visible deadline.

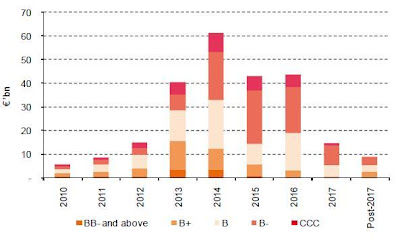

Arguably the same could not be said for the European market for leveraged loans. The peak of loan origination, the previous peak of bank-financed M&A, was in 2007 – see graphic 1.

That recent change has been a small negative is picked up by data for companies that are seeking to renegotiate their borrowings with their lenders. Graphic 3 shows a low level of restructurings and renegotiations, but against a background of some economic growth in Europe.

Addendum

6th December 2011:

MKP Capital Management LLC, the New York-based global macro and structured-credit hedge fund with $4.5 billion in assets, is starting a credit team in London to invest in European debt. Steven Jeraci, a partner at MKP, will relocate to the firm’s London office to hire investment professionals and build the team’s infrastructure, the hedge fund said in a statement today. The team should be in place by the end of next year, the company said.(source: Bloomberg News)

Comment – the fact that a team will be put in place by the end of 2012 says something about when the opportunity to commit capital will be ripe for exploitation, and reinforces the point that to build a quality team will take some time.

Addendum

25th January 2012:

Mesirow Advanced Strategies Inc., which allocates $14 billion to hedge funds, has been increasing the amount of cash it holds in the last couple of months in preparation for potential opportunities including those in the European credit markets. “What we want to have is the flexibility that if particular things do deteriorate, we can play offense relatively quickly, being able to put capital to work in interesting opportunities,” Marty Kaplan, chief executive officer of the Chicago-based fund of hedge funds manager.

Kaplan said Mesirow may also deploy more capital to relative-value strategies such as capital structure arbitrage, which seeks to profit from mis-pricing of different securities sold by the same company. Mesirow has redeemed out of some strategies that take more directional views on the markets, such as long-biased equity and event-driven hedge funds that bet on corporate activities such as mergers and acquisitions. “As the situation in Europe deteriorates, right now you don’t see tons of corporate activities because confidence in board rooms has declined,” Kaplan said. Mesirow generally favors credit over equities strategies, said Kaplan, and prefers structured credit, which tends to be mortgage-backed, over corporate credit.(source: Bloomberg News)